Island Mice Project

Why Biodiversity Matters

It is very easy to say that having a high number of species with robust populations is a good thing. But why is this a good thing? It’s important to realize different people value biodiversity for different reasons. There are two encompassing categories that biodiversity values fall under, instrumental and non-instrumental.

Instrumental value is the value that humans attribute to an object or idea based on a perception of how that object or idea can be of use to them. In this sense, the value of species lies in the ways that humans perceive them: in other words, they are valuable because they provide food, generate profit, or provide inspiring scenery for us to enjoy. Ecological, economic, and aesthetic values are a few instrumental values we can consider.

Ecological value

When we think about an ecosystem we can imagine a number of species interacting in a food web. Any given species may consume, be consumed, or interact with a number of other species. Any given species in that ecosystem helps maintain those interactions. In this way each species has an ecological value.

Economic value

This value of biodiversity is realized when humans extract something (e.g. food, chemicals) from a living organism. A common argument for conserving tropical rain forests is the possibility of using chemicals derived from undiscovered plants for medicines.

Aesthetic value

Very few people will ever see the ashy storm petrel. What is its value?

Photo: Courtesy of Wikipedia

We aesthetically value biodiversity any time we view and enjoy wildlife. Whenever we birdwatch, walk through a forest, or view a nature documentary we are valuing the aesthetic value of biodiversity.

A non-instrumental value is a little bit tougher to think about. A non-instrumental value means that people receive nothing by valuing a given object or idea. As the word ‘noninstrumental’ suggests, people don’t get anything out of it. The concept of intrinsic value is often attributed or substituted for noninstrumental value. Intrinsic value means that something is good, in and of itself, regardless of what people think about said object. This is the position advocated by many environmental and animal rights advocates when discussing other living organisms.

As an example we can consider a population of petrels that nest on a remote Pacific island. People may never directly interact with the birds but we know they exist and they continue to live, breed, and die on their own. Whatever those birds do, is good for those birds. People are not a part of the equation. Once we remove ourselves from the equation and think of the petrels independently then we can consider the intrinsic value of those birds. It’s a bit easier to think of animals or objects that do not interact with people as having intrinsic value. Or try to imagine a world without people. Would that same population of petrels still have some sort of value or goodness without a person saying those birds have value?

What is Biodiversity?

Why do we value biodiversity?

Photo: Courtesy of Wikipedia

Biodiversity can be thought of as the amount of biological variation within a location. A shorthand version is simply the amount of species in a given place.1 Variation within a species also increases biodiversity. The higher the number of individuals of a species the higher the expected diversity. To maintain a high level of biodiversity there should be a high number of species as well as a significant number of individuals per species. However, there are a few other ways that we can think about biodiversity. Genetic biodiversity describes the variation of genetic sequences. Thus, having many different species of plants and animals increases genetic biodiversity. It’s also important to remember that biodiversity changes based on the size of a place. The amount of biodiversity changes when moving from islands, to continents, and to the entire planet. When talking about biodiversity people are often referring to global diversity.

References

- Maier, D. S. (2012). What’s So Good about Biodiversity?: A Call for Better Reasoning about Nature’s Value (Vol. 19). Springer.

What is an Invasive Species?

The brown tree snake is an invasive species that has caused ecosystem-level disruption on the island of Guam.

Photo: Courtesy of Wikipedia

An invasive species is a species that has been intentionally or accidentally introduced by humans to a new region. Common introduction pathways include ballast waters of transcontinental ships, cargo holds of aircraft, and the leaves and soil of nursery plants. Within a new region an invasive species disrupts ecosystem function or causes other damages. Invasive species are known to damage environmental and economic systems and cause harm to human health. Species from practically all taxonomic groups can and have been considered invasive species. In the United States species such as kudzu, Burmese python, and European starlings are common examples of species that damage ecosystems. Species such as zebra mussels and the brown tree snake cause both environmental and ecological damages.

How does an invasive species harm an ecosystem?

Invasive animals can affect surrounding species by eating them, consuming their food, competing for habitat, and introducing disease.1 Typically, a species evolves in a system with competitors, predators, and parasites. But an invasive species in a new location may not encounter any of these obstacles. Conversely, a native species that encounters an invasive species for the first time may not have any defenses prepared. Species isolated on islands may evolve island tameness.2 This means they have lost natural defenses or are naive to predators. For example, the bridled white-eye, a small bird native to the island of Guam would sleep wing-to-wing on branches and remain still as the invasive brown tree snake preyed on neighbors sitting next to them.3 This allowed the brown tree snake to eat a number of the birds without trouble. The bridled white-eye no longer occurs on Guam because of the brown tree snake.

It is important to note that many species have been moved across the globe but are not known to widely disperse or negatively affect ecosystems in their new locale. A great deal of species traverse the world and never establish themselves. That is because a species evolves within a specific set of abiotic factors (such as temperature, humidity, or water pH level).

The strawberry guava (Psidium cattleianum) is invasive in Hawai’i. But it has existed on the island for generations and was given the native Hawaiian name waiwi. Photo: By Forest and Kim Starr.

Some species are capable of overcoming abiotic changes, others are not. Ecologists study invasive species to better understand the characteristics of invasive species and the environmental circumstances that lead to successful invasions. There are still a great deal of questions to be answered regarding the success and failures of invasive species.4 Species that can survive in a new locale but don’t cause the ecological damages that an invasive does are often referred to as introduced, exotic, or non-indigenous. On the other hand, native or indigenous species are those who exist and have evolved within an ecosystem without human intervention. Similar to a native species, a species that is naturally endemic to a place only exists there.

Many species are viewed negatively simply because they are non-indigenous. Discriminating against a species only because they are introduced has been strongly debated.5 With the number of species that are being moved across the globe there is a growing concern that only invasive species with significant impacts should be targeted for containment or eradication.6 An invasive species may not be perceived as such by individuals or a community. When an invasive species has existed in a place for a long time it can even be considered native.

How do they affect islands in particular?

The brown rat is a common island invasive, but also a common pet.

Photo: Courtesy of Wikipedia

Island ecosystems are home to a high level of biodiversity but are susceptible to invasive species. Many islands, especially in the Pacific ocean, were not populated by land mammals prior to human contact. Several mammalian species have been introduced to islands across the globe, with rodents being the most commonly introduced.7 The most common invasive rodent species are black rat (Rattus rattus), brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans), and house mouse (Mus musculus).

The first eradication campaign using rodenticides began in 1959 in New Zealand.8 Since that time invasive rodents have been eradicated from over 280 islands across the globe.9 In the United States successful rodent eradications on islands have occurred on remote Pacific Ocean islands, Hawaii, Alaska, California, Florida, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.10 More information can be found in the History of Rodent Eradications section.

References

- Mack, R. N., Simberloff, D., Mark Lonsdale, W., Evans, H., Clout, M., & Bazzaz, F. A. (2000). Biotic invasions: causes, epidemiology, global consequences, and control. Ecological applications, 10(3), 689-710.

- Whittaker, R. J., & Fernández-Palacios, J. M. (2007). Island biogeography: ecology, evolution, and conservation. Oxford University Press.

- Burdick, A. (2006). Out of Eden: An odyssey of ecological invasion. Macmillan.

- Hansen, G. J., Vander Zanden, M. J., Blum, M. J., Clayton, M. K., Hain, E. F., Hauxwell, J., … & Sharma, S. (2013). Commonly Rare and Rarely Common: Comparing Population Abundance of Invasive and Native Aquatic Species. PloS one, 8(10), e77415.

- Warren, C. R. (2007). Perspectives on thealien’versusnative’species debate: a critique of concepts, language and practice. Progress in Human Geography,31(4), 427-446.

- Nentwig, W., Kuehnel, E., & Bacher, S. (2010). A Generic Impact‐Scoring System Applied to Alien Mammals in Europe. Conservation Biology, 24(1), 302-311.

- Warner, K. D., & Kinslow, F. (2013). Manipulating risk communication: Value predispositions shape public understandings of invasive species science in Hawaii. Public Understanding of Science (Bristol, England), 22(2), 203–18.

- Howald, G., Donlan, C., Galván, J. P., Russell, J. C., Parkes, J., Samaniego, A., … & Tershy, B. (2007). Invasive rodent eradication on islands. Conservation Biology, 21(5), 1258-1268.

- Thomas, B. W., & Taylor, R. H. (2002). A history of ground-based rodent eradication techniques developed in New Zealand, 1959–1993. Turning the tide: the eradication of invasive species, 301-310.

- Veitch, C. R., Clout, M. N., & Towns, D. R. (2011). Island invasives: eradication and management. IUCN,(International Union for Conservation of Nature), Gland, Switzerland.

Why Islands?

Hawai’i Mamo and other Honeycreepers Image: Courtesy of Wikipedia

Islands are land masses surrounded by water and are smaller than continents, which makes the word island an incredibly broad term. Furthermore, islands are utilized in various ways with an estimated 3.5 million people living on over two thousand individual islands spread throughout our planet. Islands are used for livelihoods, vacation destinations, and as areas for scientific research. This leads to negotiations about what to do with island ecosystems.

Madagascar Lemurs Photo: Courtesy of Wikipedia

Islands make up less than 1/6 of the Earth’s land area, but are home to an incredibly diverse range of species due to their isolation and the amount of available niche space.1 They range in size from tiny rocky outcrops to Greenland, which is hundreds of thousands of square kilometers in size. The biogeography of islands is also diverse and landscapes vary from barren land, icy mountain ranges, to lush tropical forests. Islands are often home to endemic species, species unique to a geographical location and found nowhere else. These endemic species are found on only one or two particular islands.2 Famous endemics include the Hawaiian honeycreepers, the Galapagos tortoises and the lemurs of Madagascar. Island endemics are particularly vulnerable to extinction due to invasive species, anthropogenic disturbances, and loss of habitat, and it is estimated that eighty percent of known extinctions have occurred on islands.3

Galapagos Tortoise Photo: Courtesy of Wikipedia

Islands are useful sites for scientists when learning about biota, biogeography, population colonization, and adaptation. In addition, they are often part of ongoing research that leads to the enhanced understanding of ecology and evolution. One of the reasons scientists focus on islands is that they tend to hold smaller populations that are isolated from the mainland. While islands make up a small amount of the planet’s total land area, they are home to an estimated twenty percent of all bird, reptile and plants species.4

Furthermore, they contain nearly half of all critically endangered species and extinction rates are higher on islands than on continents.4 Hence, many conservation campaigns have focused on islands.3 Conservation on islands is a combination of several factors: the types of animals viewed to be in need of conservation, the presence of humans, and the political and regulatory aspects related to the country or territory where the island is located.

City of Avalon on Catalina Island Photo By: Megan Serr

Other factors that influence conservation efforts are the size, remoteness, types and extent of economic activity, and the sociocultural influences on the island. In addition, many islands often have a long history of native people who may or may not have experienced further colonization by Europeans, at one time or another. It is a result of human travel and colonization that invasive rodents were brought to islands, and now over eighty percent of islands worldwide have invasive rodents.5 This is a direct threat for islands, as endemic species on islands have often evolved in the absence of mammals that can eat them.3

References

- G. Paulay, “Biodiversity on Oceanic Islands : Its Origin and Extinction,” Am. Zool., vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 134–144, 1994.

- Blackburn, T. M., N. Pettorelli, T. Katzner, M. E. Gompper, K. Mock, T. W. J. Garner, R. Altwegg, S. Redpath, and I. J. Gordon. 2010.Dying for conservation: eradicating invasive alien species in the face of opposition. Animal Conservation 13:227–228

- Grosholz, E. D. 2005. Recent biological invasion may hasten invasional meltdown by accelerating historical introductions.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102:1088–1091.

- Keiit, B. Campbell, K. Saunders, A. Clout, M. Wang, Y. Heniz, R. Newton, K. Tershy, B. The Global Islands Invasive Vertebrate Eradication Database: A tool to improve and facilitate restoration of island ecosystems. Island Vetebrate Eradication Database. 2011.

- A. Anderson, “The rat and the octopus: initial human colonization and the prehistoric introduction of domestic animals to Remote Oceania,” Biol. Invasions, vol. 11, no. 7, pp. 1503–1519, Dec. 2008.

The Human-Mouse Relationship

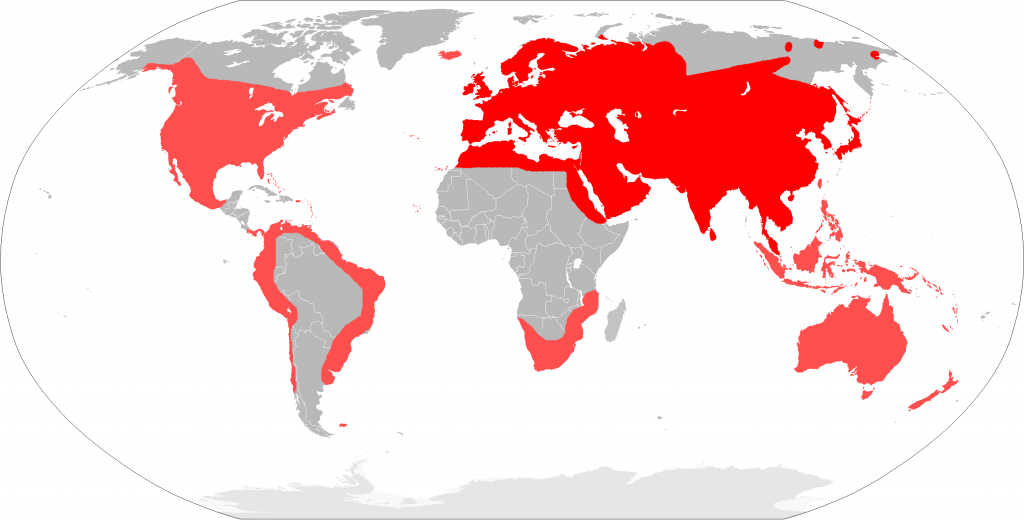

The relationships and viewpoints that people have towards rodents, in particular the mouse, is complicated. Mice may be the animal with the longest and closest relationship to humanity, but it is not always a happy relationship. On one hand, the mouse has become the mascot for amusement parks, and many pet stores sell mice and rats as pets. On the other hand, these animals are considered pests, and most people can recognize a mousetrap. Rodents have been associated with humans since the advent of agriculture. House mice having originally been adapted to rocky outcrops and feeding on seeds were primed to come along to human structures filled with seeds.1 House mice (Mus musculus) originated around 900,000 years ago, in what is now Southern India.2 Since that time the species has spread as a result of human colonization and now three main subspecies exist, M.m. domesticus, M.m castaneus, and M.m musculus.1 As a consequence of rodents being associated with humans and human settlements, house cats may have domesticated themselves by preying on the mice found in human agricultural environments.3

Distribution of the house mouse (Mus musculus) Photo: Courtesy of Wikipedia

Humans, while beneficial, are not essential for rodents to survive. In particular the Black rat (Rattus rattus), the Brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), and the House mouse (Mus musculus) are considered pests, and these non-native rodents can be found on over eighty-percent of islands worldwide.4 Humans did not intend to spread mice throughout the globe, but rodents nevertheless dispersed widely as stowaways on ships, rafts, and other means of transportation.5 [See Why are Mice so Invasive? and History of Eradication]

The pet or fancy mouse has been quite an allure to humans for centuries now. Records of different mouse spots, colors and morphs were even depicted by the ancient Egyptians.2 In Japan during the 1700’s the breeding of various strains of mice for coat color and other characteristics became popular. Then in the 1800’s this trend spread to Europe. This led to the National Mouse Club in England, which is still active today.2 In some cultures rodents are sold, traded, and even worshipped.

House mice have been bred to show large amounts of phenotypic variation. Photo: Courtesy of Wikipedia

A temple in Rajasthan, India is devoted to rats. It was built in the 1910’s and is a tribute to the Rat goddess Karni Mata.6 In North America the breeding of mice expanded beyond the pet trade when mice became used for science and in the laboratory setting.2 Today researchers everywhere have their own strains of rodents, and mice are the most common mammals used in research.2 Mouse strains are types of mice inbred for certain characteristics for generations. Suppliers such as Jackson laboratories, Charles River laboratories, and Taconic farms house thousands of different mouse strains used globally for research. An advantage with mice is the standardization of strains such as the C57BL/6(abbreviated B6). Standardized strains eliminate the chance of genetic variability as a factor when analyzing experiments, and different experiments may rely on different strains to analyze particular dynamics.2 At the same time however, laboratory strains of mice such as the B6 that have been inbred for desired traits now bear little resemblance in behavior to wild mice [See SRY cost]. Overall, humans and mice have a long-standing relationship, which began with the rise of agriculture, and has gone in various directions from research model to scourge.

References

- Pocock, M. Searle, J. White, P. 2004. Adaptations of Animals to Comnensal Habitats: Population Dynamics of House Mice mus musculus domesticus on Farms.

- L. Silver, 1995. Mouse Genetics The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor Maine http://www.informatics.jax.org/silver/index.shtml

- Driscoll, C. Macdonald, D. O’brien, S. 2009. From wild animals, to domestic pets, an evolutionary view of domestication. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences. 106(suppl 1) 9971-9978.

- MacKay, J. Russel, B. 2007. Eradicating house mice from islands. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services.http://www.aphis.usda.gov/wildlife_damage/nwrc/symposia/invasive_symposium/content/MacKay294_304_MVIS.pdf

- Driscoll, C. Macdonald, D. O’brien, S. 2009. From wild animals, to domestic pets, an evolutionary view of domestication. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences. 106(suppl 1) 9971-9978.

- Guynup, S. Ruggia, N. 2004. Rats Rule at Indian Temple. National Geograhic News. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/06/0628_040628_tvrats.html

Why are Mice so Invasive?

There are very few studies characterizing how and why house mice are successful at invading and adapting to island environments. In part, the lack of information is due to their small size – compared to the devastating visible effects goats and pigs have on flora and fauna, mice have few immediately visible impacts.1

Caroline Leitschuh holding a pup from invasive mice captured from the Farallon Islands

Photo By: Megan Serr

One well-characterized behavior of introduced house mice is feeding behavior. Studied extensively in the sub-Antarctic region, house mice there have deviated from the grass and seeds diet typical of the species. Instead, they predominantly eat larvae, worms, and insects. On some islands, they do eat young plant shoots and seeds during the late spring and early summer period, but over half their diet is still composed of non-plant material. As their name suggests, sub-Antarctic islands are cold, and the mice there may have higher metabolic needs which contribute to needing a higher-calorie diet.2 However, introduced house mice on islands in more temperate regions have been shown to prefer insects and seabirds. This preference generally happens when other food sources are scarce, suggesting that mice are adaptable in terms of diet, which helps them establish on islands with a variety of food sources.3

Beyond their feeding habits, little is understood about the behaviors of the house mouse in the absence of human-provided food sources and shelter. There is evidence that house mice breed year-round with access to human-made shelter and food.4 When introduced on islands with native species that have not evolved in the presence of predators, the mice may have access to abundant food sources.5 However, little research has been done to directly address why mice are such successful invaders. While it is anecdotally apparent that mice are highly invasive, a better characterization of their behavior is needed to understand why.

References

- Angel, A., Wanless, R. M., & Cooper, J. (2007). Review of impacts of the introduced house mouse on islands in the Southern Ocean: are mice equivalent to rats? Biological Invasions, 11(7), 1743-1754.

- Smith, V. R., Avenant, N. L., & Chown, S. L. (2002). The diet and impact of house mice on a sub-Antarctic island. Polar Biology, 25, 703-715.

- Le Roux, V., Chapuis, J.-L., Frenot, Y., & Vernon, P. (2002). Diet of the house mouse (Mus musculus) on Guillou Island, Kerguelen archipelago, Subantarctic. Polar Biology, 25, 49-57.

- Rowe, F. P., Taylor, E. J., & Chudley, A. H. J. (1964). The numbers and movements of house-mice (Mus musculus L.) in the vicinity of four corn-ricks. Journal of Animal Ecology, 32(1), 87-97.

- Case, T. J., & Bolger, D. T. (1991). The role of introduced species in shaping the distribution and abundance of island reptiles. Evolutionary Ecology, 5, 272-290.