NC State Spinout Company Seeks to Spark Innovation, Fight Food Waste

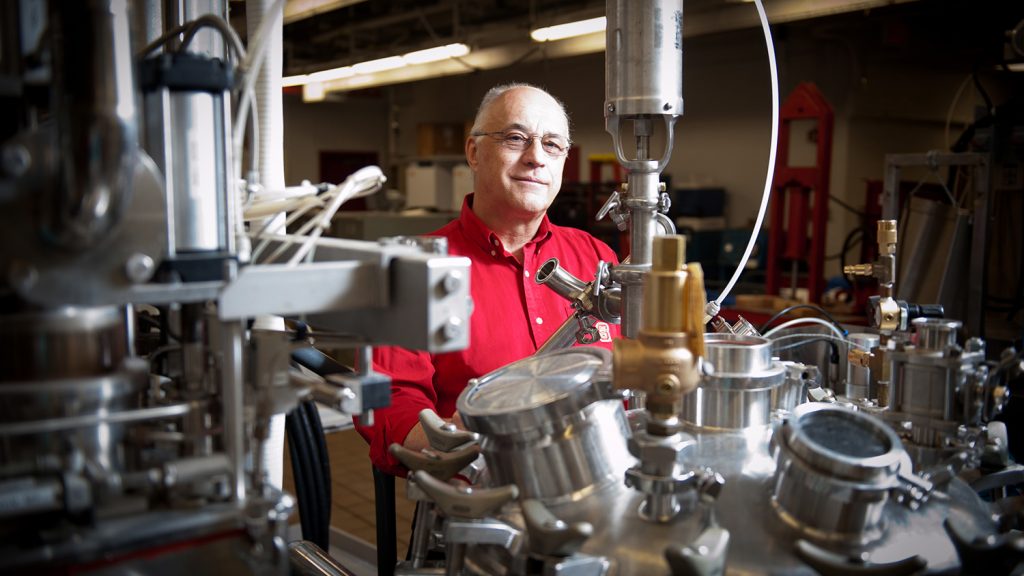

When food science professor Josip Simunovic applied to the Chancellor’s Innovation Fund, he wanted to build a machine. A machine that would allow other inventors like himself to get new products to market faster — and at a fraction of the cost.

SinnovaTek, a company he co-founded, has now helped bring more than 100 new FDA-approved products to market.

“Usually, it takes about a couple of years to get on the market, and we can do it in six months to a year. That’s never been done before,” says quality manager Elaine Howell, who earned her bachelor’s in food science at NC State University and is one of several State grads SinnovaTek now employs.

Simunovic, a research professor in NC State’s College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, launched SinnovaTek in 2015 with his former student Amanda Vargochik, who serves as the company’s chief innovation officer, as well as Michael Druga, who serves as CEO.

“Back when this whole thing started, we really didn’t anticipate the way it would develop,” says Simunovic, who earned his Ph.D. from NC State in 1998 and now holds dozens of patents.

He says in the beginning, the goal was “to maximize nutrient retention” — and quality — especially in products like baby foods, which were relatively overlooked. One of the first foods they tested was puréed sweet potato.

“The technology used before retained less than 30% beta carotene,” Simunovic says. “When we did our trials, it was 97-98%.”

Along the way, they realized that the technology had the potential to help curb food waste, too.

According to USDA estimates, close to one-third of food goes uneaten in the U.S. each year at the retail and consumer level. While food that gets tossed to the trash in homes and restaurants accounts for much of this waste, plenty more loss occurs throughout the supply chain — particularly in the produce industry.

In North Carolina, Druga says as much as 40% of sweet potatoes grown by farmers used to go to waste.

Perfectly edible fruits and veggies can get left behind for various reasons. Oftentimes, it’s simply due to supply and demand. If the market price is too low to justify the cost of harvesting and transporting the crops, or if there aren’t enough workers to harvest them, they often get left in the fields. But sometimes it’s because the crops aren’t quite the right size or just don’t look good enough to sell in stores.

That’s where companies like SinnovaTek can step in to help.

A Certified B Corporation and member of the UpCycled Food Association, each year SinnovaTek helps turn millions of pounds of food once destined to rot into products such as protein gummies and purées or soups, smoothies and sauces.

One new client alone, which is “coming online” this year, now brings them close to 10 million pounds of carrots that would otherwise go to waste.

“Eight million pounds a year that we can turn into a beautiful purée,” Druga says.

Roots of the Research

Processed food gets a bad rap. The truth is, though, plenty of processed foods can now be made to taste as if they were freshly prepared and can also pack just as much nutrition — while remaining shelf-stable throughout shipping and months of storage.

That’s largely thanks to the advent of microwave processing and many subsequent innovations, several of which were pioneered by NC State food scientists like Simunovic.

Microwave processing — known in technical terms as “continuous flow microwave pasteurization and sterilization” — is a type of aseptic processing, a system for quickly heating and packaging food products in a sterile environment.

Using the same kind of energy as the microwave in your home, Simunovic and SinnovaTek’s patented technology can evenly cook thick, viscous foods with indirect heat — resulting in products that retain more nutrition and flavor.

In 2014, Simunovic received support from the Chancellor’s Innovation Fund, a competitive internal seed funding program NC State created to guide ideas from the research lab into the business world. The CIF aims to bridge the gap between public and private funding; it’s designed to help develop a technology to the point that it can be licensed or a startup can be formed.

Simunovic, Vargochik and Druga launched SinnovaTek roughly a year later.

Where They Are Now

Through its subsidiary FirstWave Innovations, SinnovaTek now helps other inventors and small companies get their novel products to market — guiding them through the commercialization process.

“The CIF is similar to what we’re doing here now,” Simunovic says. “That category didn’t really exist for aseptic processing until this was put in place.”

The modular machines SinnovaTek builds and sells can put out “anywhere from two to five liters per minute” — which are called “precision-scale processors” and make up most of the equipment at FirstWave — to as much as the “20-30 gallons per minute” that its largest systems can generate, Simunovic says.

This allows companies of all sizes to test, launch and eventually scale up products much faster than average — and for far less money upfront.

“In the aseptic food space, you need to be at millions of units to even test-market a product. It’s just a lot of risk,” says Vargochik, who earned her master’s in food science from NC State. “So we’ve provided a model where companies can lower their risk.”

FirstWave has no minimum-order requirement.

Why? To help “better products” get to market. “It’s definitely our focus to bring young brands into the market because we find there’s a lot of innovation there,” Vargochik says.

Druga says that while most of SinnovaTek’s competitors go after products like applesauce — which are popular and therefore safer, but at the same time, “aren’t differentiators” — SinnovaTek focuses more “on small-scale entrepreneurs looking to launch new, innovative products.”

“Something that’s better for you and unique, not just a combination of artificial flavors and sugars,” Druga says. “We really try to get more into natural products and leverage the technology to do that.”

SinnovaTek also works with big players in the industry, too, though. Druga says they recently helped a Fortune 500 company get from “idea to store shelf within three months.”

“And now we’re going to launch a commercial product for them in less than a year, with virtually no capital out of pocket for them,” Druga says, as opposed to the two to three years and few million dollars it normally takes. “So that’s really what the model enables: Rapid prototyping for food innovation.”

The smaller, mobile microwave processors SinnovaTek makes are good for more than just pilot-testing new products, though. They’re also ideal for those who need the ability to process leftover produce immediately and on-site.

“One of the biggest issues with waste streams right now is trying to preserve them long enough to be able to use them,” Druga says.

For example, Druga says the wet skins and peels that are byproducts of a typical juice production system go bad within hours.

The SinnovaTek team knows there’s still lots of nutrients left in these types of byproducts, too. They’ve shown that when combined with protein, the skins of blueberries and muscadine grapes can be transformed into nutrient-rich gummies.

In 2019, SinnoVita, another subsidiary of SinnovaTek, partnered with Ripe Revival — founded by NC State Poole College of Management alumnus Will Kornegay — to launch a line of fruit gummies, which are not only made from food waste but also high in protein and allergy-friendly.

The technology behind the gummies evolved from research that began in the labs of Simunovic and Mary Ann Lila, director of NC State’s Plants for Human Health Institute in Kannapolis.

But it was Nathalie Plundrich, now SinnovaTek’s technology development manager, who first thought to apply the technology to create gummies. Plundrich, who earned her master’s and Ph.D. in food science from NC State, studied the technology when she was a student in Lila’s lab. When Plundrich joined SinnovaTek in 2018, she brought that knowledge with her.

How the Chancellor’s Innovation Fund Helped

Things have come a long way since Simunovic received support from the Chancellor’s Innovation Fund (CIF) in 2014. He credits the SinnovaTek team for much of the progress that’s been made over the years.

But it was the CIF’s early-stage support that allowed him to build the initial prototype of the precision-scale microwave processors now housed in FirstWave’s facility off Atlantic Avenue.

And Simunovic says that prototype equipment is still in use today, too, by students in his lab.

Additionally, beyond the financial support Simunovic received, Druga and Vargochik say NC State’s Office of Research Commercialization has remained an ally since SinnovaTek’s inception. For example, the Office of Research Commercialization invited the trio to be a part of NC State’s first-ever National Science Foundation I-Corps cohort, in 2017.

A Continued Partnership

SinnovaTek continues to work closely with the Office of Research Commercialization — licensing almost 20 existing patents and regularly seeking to file new ones.

“We work very closely with Kultaran [Chohan] and the group there to make sure we have the right licenses, to make sure that we’re able to support the IP,” Druga says. “We’ve also continued growing the IP portfolio. We’ve actually created several new patents that are shared with NC State, because of the shared ownership with Josip. So it’s always been a collaborative effort.”

What’s more, SinnovaTek got backed by the Wolfpack Investor Network in August. Leveraging the NC State community’s powerful opportunities for networking and guidance from industry experts and successful business leaders, the Wolfpack Investor Network — made up of NC State alumni and others in our entrepreneurial community — matches investors who have relevant expertise with companies in its portfolio.

What’s Next

SinnovaTek is still growing, almost as fast as their microwave processors can churn out food. Druga says one of their co-packing partners sells its baby food in Whole Foods across the country — and is “growing like crazy.” So to keep pace with demand, SinnovaTek needs more space.

The company plans to open a brand-new, 62,500-square-foot production plant by the end of the year.

Druga says they’ll start out with “a line similar to the one” in FirstWave’s current, 9,000-square-foot facility, which will remain in operation. The machines at the new plant will run “about five times faster,” though, Druga says. Down the road, Druga says they’ll add “more production lines and new package formats.”

But in one key way the equipment will be exactly the same — all-electric.

“We believe very strongly in electric heating because it can run from sustainable energy sources,” Druga says.

Simnunovic says they’ve been getting “calls from all over the world” about their technology and how it plays into global efforts of “decarbonization through electrification.”

Sustainability is paramount to SinnovaTek’s mission, and the company also wants to continue expanding its reach internationally. It’s already made a difference in Africa, where one of its microwave processors is being used to make shelf-stable sweet potato purée.

With help from Tawanda Muzhingi, an adjunct professor in the Department of Food, Bioprocessing and Nutrition Sciences, SinnovaTek shipped one of its “Nomatic” processors to Kenya in 2020.

The company was recognized for this work with a Tibbetts Award from the U.S. Small Business Administration. It’s work like this that inspired Plundrich to join SinnovaTek after finishing her Ph.D. at NC State.

“I don’t want to just develop the next chip flavor or something,” Plundrich says. “I want to be part of something bigger.”

However, while they want to make impacts worldwide, when picking a location for their new plant, Druga says it was also important to stay close to campus. The new production plant will be located in Middlesex, North Carolina, roughly a half-hour drive from Raleigh.

Druga says they plan to hire as many as 50 new employees within the first two years of opening the new plant, which would more than double their staff. It’s almost certain that more than a few of these new-hires will be products of NC State.

This post was originally published in NC State News.