How ITRE Has Helped Traffic Engineers Build Better Diverging Diamond Interchanges

Five civil engineering experts from NC State University’s Institute for Transportation Research and Education (ITRE) contributed to the latest official guidance on designing diverging diamonds, an "alternative interchange" that’s quickly become more common around the nation.

If you’ve exited Interstate 440 onto Western Boulevard coming to campus lately, you might have noticed some changes.

What was once a tight loop is now a straighter, standard offramp thanks to a popular new road design — the diverging diamond interchange — that’s been tested in a driving simulator right here at NC State.

“A diverging diamond interchange allows two directions of traffic to temporarily cross to the left side of the road. [It] allows free-flowing turns . . . eliminating the left turn against oncoming traffic and limiting the number of traffic signal phases,” according to the North Carolina Department of Transportation. More importantly, it prevents “last-minute lane changes” and “provides better sight distance at turns” in hopes of reducing crashes.

If you haven’t yet driven down Western Boulevard under I-440, however, you might not have noticed much difference at all. It’s going under the bridge where the opposite lanes of traffic on Western now briefly crisscross. Eventually though — after every cone’s been picked up and each line’s been painted down — even the at-first counterintuitive act of driving on the “wrong” side of the road should become second nature.

“You don’t know any different while you’re doing it — you’re just driving down the road,” says Chris Cunningham, director of system designs and operations at the Institute for Transportation Research and Education. “Once the final design is in place, most people don’t even know they’re driving through it.”

The diverging diamond interchange at Western Blvd. and I-440 — the first in the Triangle region — opened in November. Like anything new, navigating it can take some getting used to. But research shows that diverging diamonds, while unconventional, can be safer and more efficient in a number of ways. And much of that research has been done with the help of NC State University civil engineering researchers.

“We’ve played a lead role in researching this topic nationally,” says Billy Williams, director of the Institute for Transportation Research and Education (ITRE).

In fact, Cunningham, who’s also a program director at ITRE, was the principal investigator for the research behind the Diverging Diamond Interchange Informational Guide, Second Edition, published by Transportation Research Board’s National Cooperative Highway Research Program. ITRE’s Chris Carnes, Thomas Chase, Yulin Deng and Kihyun Pyo also contributed to the work (along with others from outside NC State).

According to that research, published in 2019, the diverging diamond interchange (DDI) design reduced crashes by an average of almost 40% after it was constructed in 26 places across the U.S. And the rates of injury and fatal crashes, on average, fell by over 50%.

“We’ve played a lead role in researching this topic nationally”

There were three main goals for what would become the second edition of the DDI informational guide. Ensuring and increasing safety for drivers was first, foremost — and a common theme among all three.

“We took all the designs that we’d looked at across the U.S. and we got crash data, and we determined under which criteria they were safe and which criteria they were not,” Cunningham says.

Cunningham says they were also tasked with determining the optimal way to time traffic signals at DDI intersections.

“We wanted to help engineers know how to time the signals efficiently based on where the volumes of traffic are going to come from,” Cunningham says. “Because it was a new design, it wasn’t a simple thing.”

And third, Cunningham says they were asked to help with how to best “geometrically design” diverging diamonds. That’s when the driving simulator, now housed in Fitts-Woolard Hall, came into play.

“We used our driving simulator to look at how to design the interchanges such that people looked, for instance, in the correct direction,” Cunningham says.

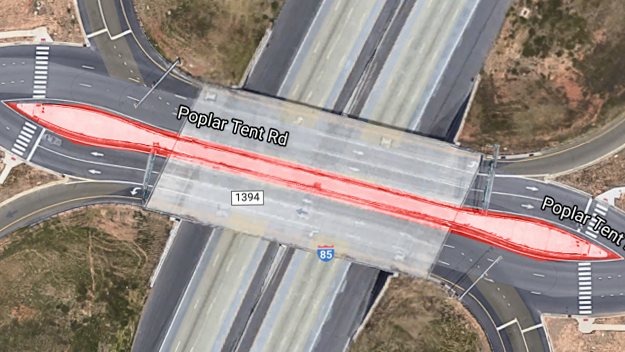

In other words, to help keep drivers from getting disoriented they needed to figure out how to always create enough of an angle so that, for example, you know which way to watch for oncoming traffic when merging from the right (pictured below).

The solution: a “Q-tip”-shaped median.

In recent years, dozens of diverging diamonds have been built nationwide — with well over 120 in use today and hundreds more either under or planned for construction. Fourteen are now operational across North Carolina, and at least two more are planned for construction in the Triangle, one of which will be located near Raleigh-Durham International Airport. (To give a sense of how quickly DDIs gained popularity, the Western Boulevard-I-440 DDI didn’t even make it onto this map.)

So, why did the diverging diamond — which is believed to have originated in 1970s France — take off seemingly all of a sudden?

Not only do DDIs decrease crashes and clogged traffic, but they also cost less to build. Cunningham says that, usually, they can fit within the existing right-of-way and there’s also often less demolition to do.

“You can use the existing structure in most cases,” Cunningham says. “We don’t have to tear down the bridge.”

Plus, DDIs tend to be more pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly, because eliminating what experts call the “left-turn pocket” creates room for alternate modes of transportation.

“In most cases, you actually gain an extra lane or so of right-of-way with it,” Cunningham says. “You want to put a bike lane there? Go ahead. Extra sidewalk? Not a problem.”

The design allows for crosswalks, as well. Typically, pedestrians can never safely cross the road at an interchange — “but you can with a DDI,” Cunningham says.

The 2019 research was sponsored by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, in cooperation with the Federal Highway Administration.

Visit this NCDOT webpage to learn more about diverging diamond interchanges, including where else you’ll find them throughout the state.

- Categories: