Faculty Member Uses Dyes to Research Degenerative Diseases

When the average person thinks of dyes, they likely think of hair and textiles. Associate Professor Nelson Vinueza knows they have the power to do so much more.

“I build bridges between different research fields to see how we can make dyes more useful,” Vinueza says of his research group at the Wilson College of Textiles.

It is this ability to push impactful and interdisciplinary research forward that played a huge role in NC State University’s decision to name him a University Faculty Scholar in 2022.

From forensics to disease

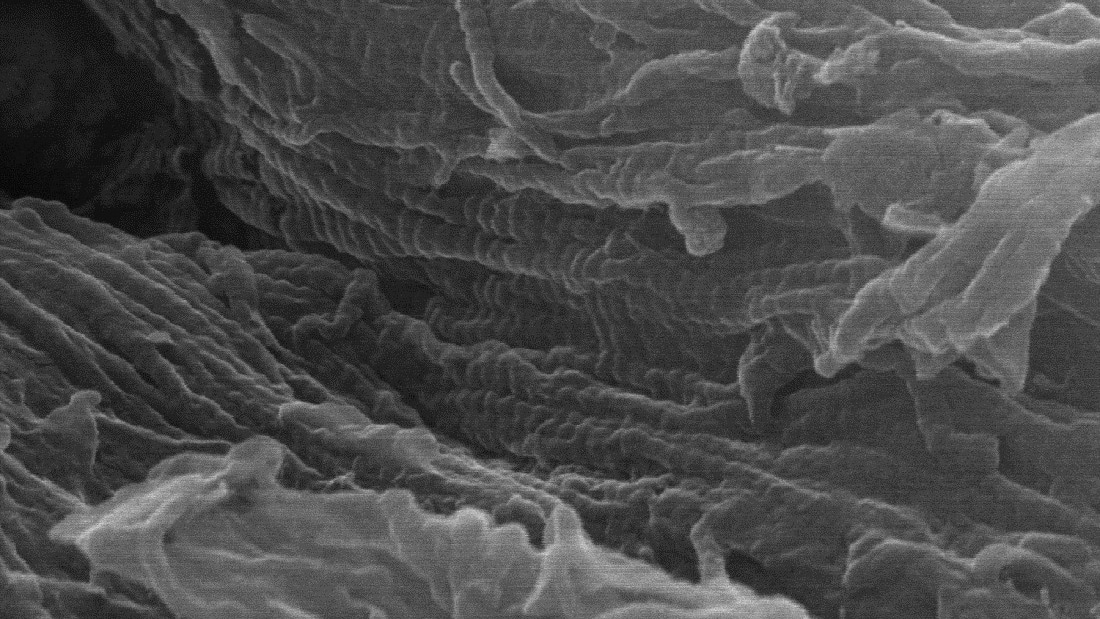

Vinueza, who holds a joint faculty appointment in the Wilson College and the College of Science’s Department of Chemistry, was first recruited to NC State University for his expertise in analytical, organic and forensic chemistry as part of the Chancellor’s Excellence Faculty Program. By using analytical chemistry, forensic scientists can determine the substances present in clothes, upholstery and other textiles in order to provide more evidence to investigators. Vinueza Labs focuses specifically on developing ways to discern information from trace amounts of dye present on tiny fiber samples – shorter than a millimeter, to be exact.

Vinueza says what drew him to NC State over other institutions was the wide range of interdisciplinary research he could engage in because of the college’s focus on all aspects of textiles. He quickly focused on figuring out how he could apply his specialization in analytical and organic chemistry to a diverse range of research interests for Vinueza Labs.

“When I identify a research gap that I can close, that’s when research becomes really exciting to me, because that’s when I know I have something to give to society,” he says.

He’s identified one such research gap within sustainability: researching how the use of dyes impacts our planet.

“I want to know what happens to a dye that is in a fabric and how it bio-degrades into the soil to understand landfill degradation with textiles and their potential role as emerging contaminants,” he explains.

His largest ongoing research project, however, could make a significant impact on health and medicine. Through a project funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Vinueza and his team of researchers are working with scientists from the University of California at San Francisco to identify potential treatments for degenerative diseases such as cataracts.

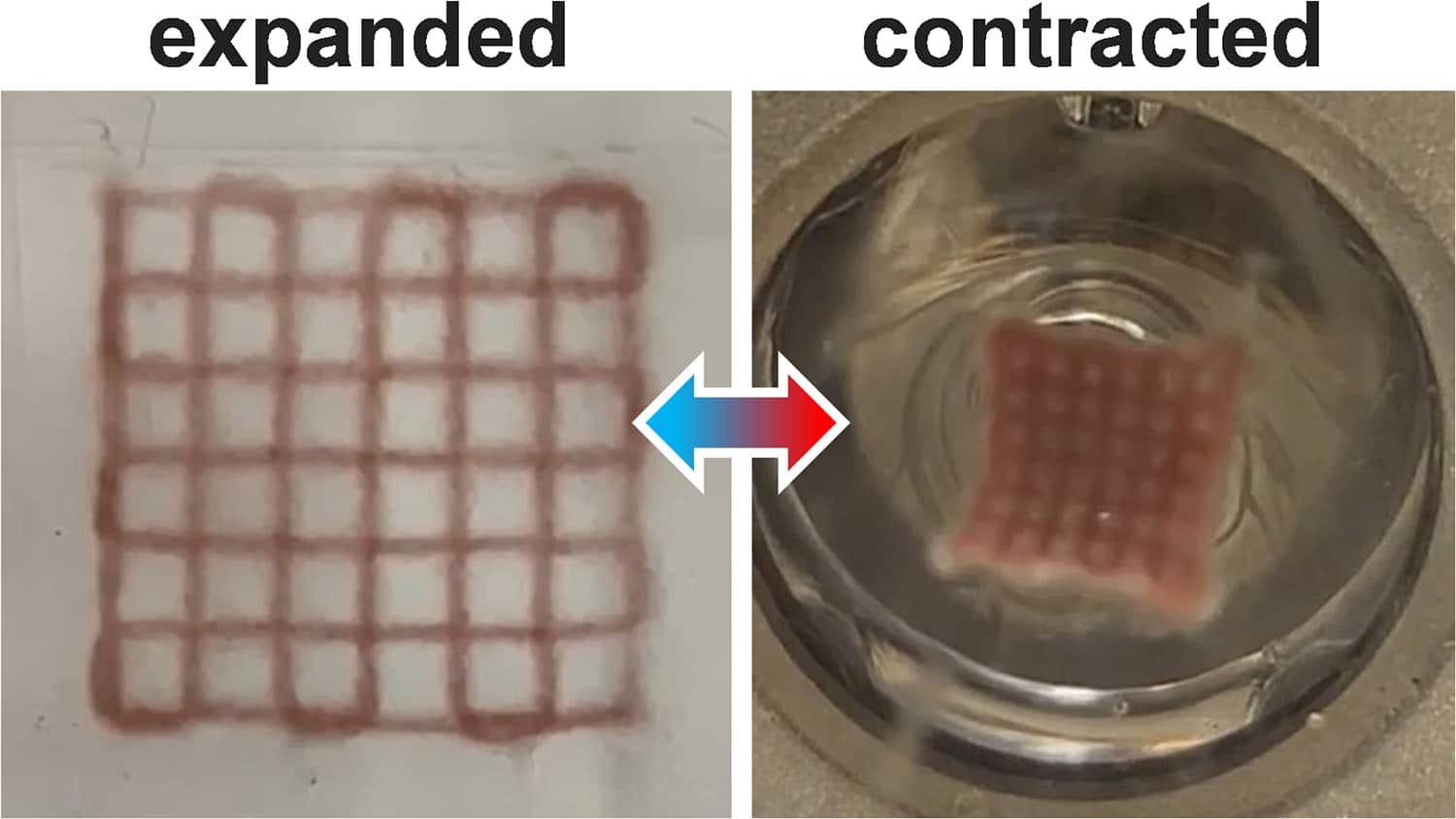

“In this case, this research uses Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF), which is a particularly versatile technique which reports protein thermal unfolding via fluorogenic dye. The dye acts as a sort of probe to help us see if a protein is unfolding,” he says.

A one-of-a-kind research resource

The NIH project is just one of a number that has been made possible by the Max A. Weaver Dye Library, where Vinueza serves as director.

The library houses a collection of dye fabric samples, testing data and more than 90,000 dyes donated by industry giant Eastman Chemical in 2014. The dyes, which were created over a period of 40 years, were custom manufactured, meaning that they provide one-of-a-kind research data.

Naturally, this has made the library a destination for researchers from prestigious universities across the world, including Johns Hopkins to the University of Leeds. And much of Vinueza’s work aims to make this library an even more useful tool for these visitors. Research assistants in Vinueza Labs are not only digitizing the library but also helping to identify connections for those using it. This unique dye database, which now includes nearly 8,000 dyes, is being used for more than a dozen collaborations outside NC State.

Fostering independent researchers

Despite the amount and caliber of research he publishes now, Vinueza began his doctoral program at Purdue University with no aspirations of becoming a professor.

“My goal was to finish my Ph.D., go back to Ecuador, and make my career in industry because that’s what we’re all about. In Ecuador, we want to have something more. We want to have our own company or business,” Vinueza says. “In my case, my aim was to open a cosmetic company.”

Purdue and his advisor, however, quickly opened his eyes to the possibilities of research and made him realize his love of mentoring and teaching.

It’s no surprise, then, that Vinueza takes a purposeful and thoughtful approach to his research assistants’ experience in his research group.

“The way I mentor my students on the graduate level is that they have to become independent scientists who solve problems,” he says.

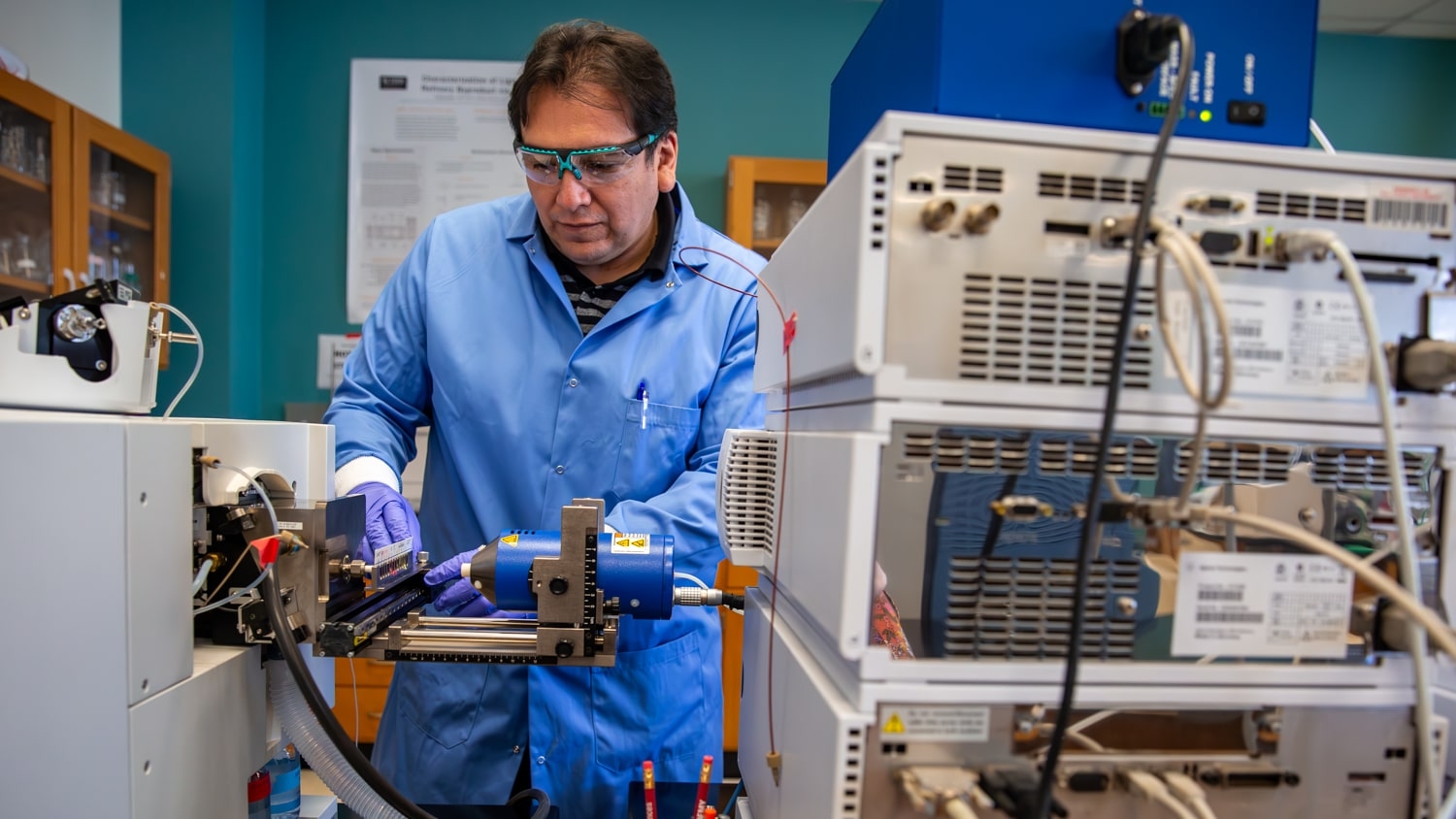

In order to do that, he assigns each graduate student responsibility for a different mass spectrometer within his lab each year. Students gain hands-on experience with these sophisticated instruments, learning how they work and how to troubleshoot or repair them.

“You can learn about instrumentation by learning how to operate, fix and adapt new hardware,” he explains. “You also become familiar with having a leadership role and solving problems because you become the go-to person for other people in the lab on that piece of equipment.”

Vinueza’s graduate students also play a crucial role in providing initial training for undergraduate research assistants. He pairs each undergraduate student with a graduate student whose project matches their interests and experience.

“My research team takes care of each other and everybody has each other’s back,” he says. “If something goes wrong, everybody helps.”

Despite all his success in research, it’s the seeing growth in his students that Vinueza says motivates him to do his best each day.

“I see the value of every person here, and that’s what I’d like to promote,” he says. “I think the most rewarding outcome of my work is to see later how successful your students become.”

This post was originally published in Wilson College of Textiles News.