3D Printing of Light-Activated Hydrogel Actuators

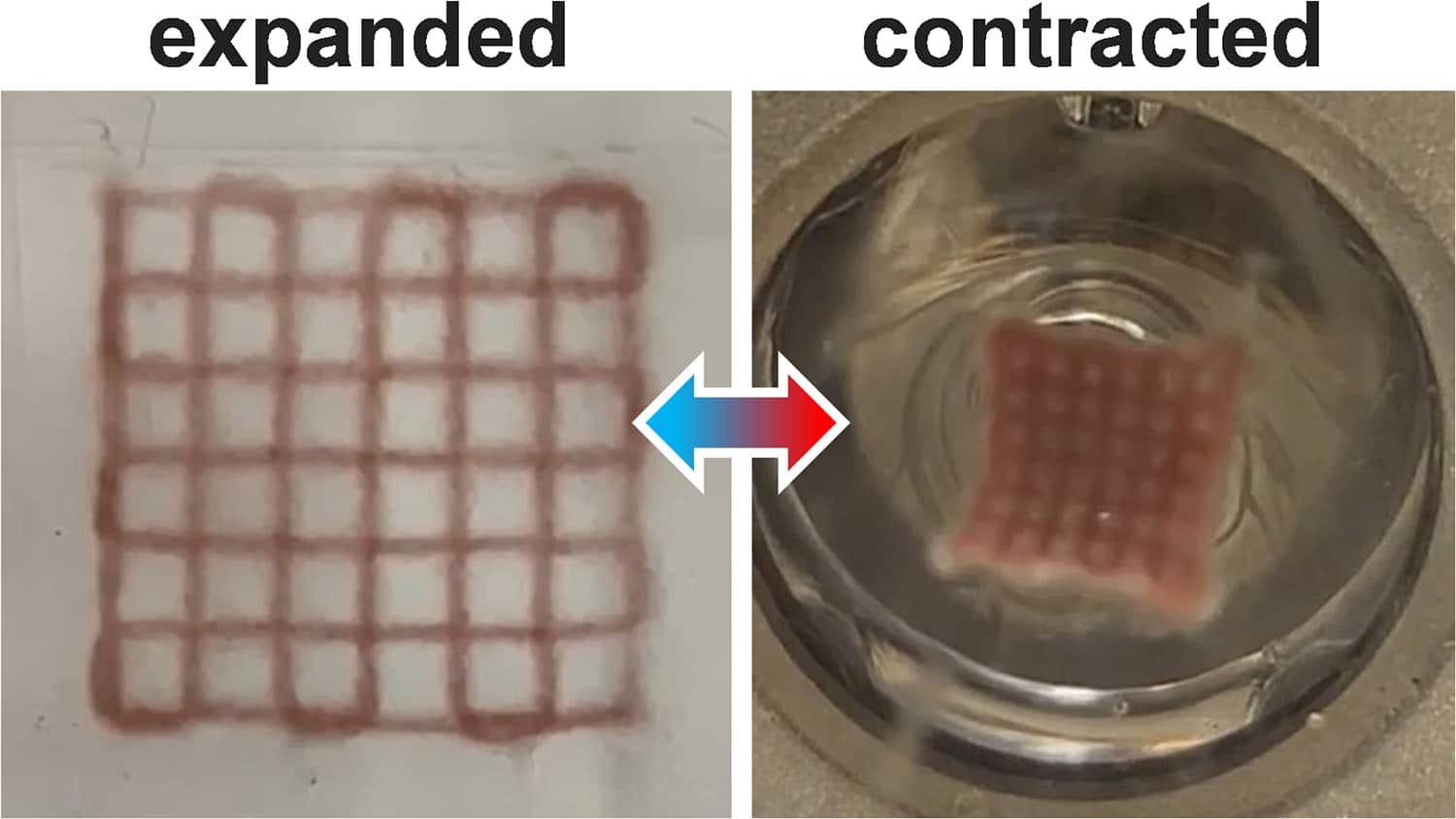

An international team of researchers has embedded gold nanorods in hydrogels that can be processed through 3D printing to create structures that contract when exposed to light – and expand again when the light is removed. Because this expansion and contraction can be performed repeatedly, the 3D-printed structures can serve as remotely controlled actuators.

“We knew that you could 3D print hydrogels that would contract when heated,” says Joe Tracy, co-corresponding author of a paper on the work and a professor of materials science and engineering at North Carolina State University. “And we knew that you could incorporate gold nanorods into hydrogels that would make them photoresponsive, meaning that they would contract in a reversible manner when exposed to light.

“We wanted to find a way to incorporate gold nanorods into hydrogels that would allow us to 3D print photoresponsive structures.”

Hydrogels are polymer networks that contain water. Examples include everything from contact lenses to the absorbent material used in diapers. And, technically, the researchers didn’t print a hydrogel with the 3D printer. Instead, they printed a solution that contains gold nanorods and all of the ingredients needed to create a hydrogel.

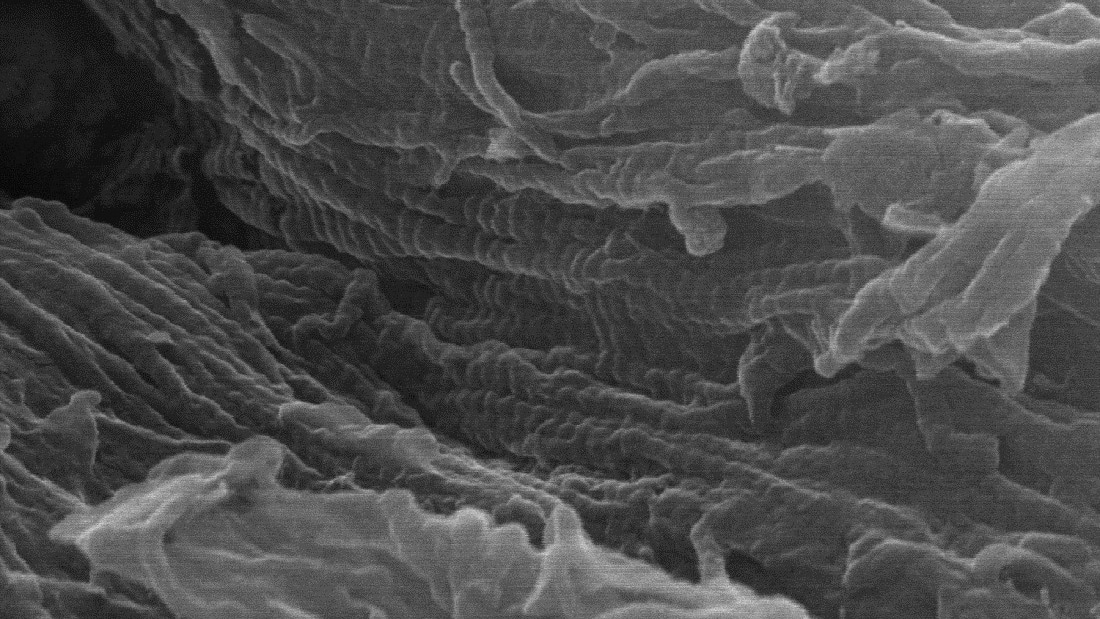

“And when this printed solution is exposed to light, the polymers in the solution form a cross-linked molecular structure,” says Julian Thiele, co-corresponding author of the paper and chair of organic chemistry at Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg. “This turns the solution into a hydrogel, with the trapped gold nanorods distributed throughout the material.”

Because the pre-hydrogel solution coming out of the 3D printer has a very low viscosity, you can’t print the solution onto a regular substrate – or you’d have a puddle instead of a 3D structure.

To solve this problem, the researchers printed the solution into a translucent slurry of gelatin microparticles in water. The printer nozzle is able to penetrate the gelatin slurry and print the solution into the desired shape. Because the gelatin is translucent, light can penetrate the matrix, converting the solution into a solid hydrogel. Once this is done, the entire thing is placed in warm water, melting away the gelatin and leaving behind the 3D hydrogel structure.

When these hydrogel structures are exposed to light, the embedded gold nanorods convert that light into heat. This causes the polymers in the hydrogel to contract, pushing water out of the hydrogel and shrinking the structure. However, when the light is removed, the polymers cool down and begin absorbing water again, which expands the hydrogel structure to its original dimensions.

“A lot of work has been done on hydrogels that contract when exposed to heat,” says Melanie Ghelardini, first author of the paper and a former Ph.D. student at NC State. “We’ve now demonstrated that you can do the same thing when the hydrogel is exposed to light, while also having the capability to 3D print this material. That means applications that previously required direct application of heat could now be triggered remotely with illumination.”

“Instead of applying conventional mold casting, 3D printing of hydrogel structures offers nearly unlimited freedom in design,” says Thiele. “And it allows for preprogramming distinct motion during light-triggered contraction and expansion of our photoresponsive material.”

The paper, “3D-Printed Hydrogels as Photothermal Actuators,” is published in the open access journal Polymers. The paper was co-authored by Jameson Hankwitz, a former graduate student at NC State; Martin Geisler, Niclas Weigel, Nicolas Hauck and Jonas Schubert of the Leibniz Institute of Polymer Research Dresden; and by Andreas Fery of the Leibniz Institute of Polymer Research Dresden and Technische Universität Dresden.

This research was done with support from the National Science Foundation, under grant 1803785; the German Research Foundation (DFG) Research Training Schools 1865: Hydrogel-based microsystems and 2767, under project number 451785257; the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation; the Dresden Center for Intelligent Materials; and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, under grant 852065.

-shipman-

Note to Editors: The study abstract follows.

“3D-Printed Hydrogels as Photothermal Actuators”

Authors: Melanie M. Ghelardini, Jameson P. Hankwitz and Joseph B. Tracy, North Carolina State University; Martin Geisler, Niclas Weigel, Nicolas Hauck and Jonas Schubert, Leibniz Institute of Polymer Research Dresden; Andreas Fery, Leibniz Institute of Polymer Research Dresden and Technische Universität Dresden; and Julian Thiele, Leibniz Institute of Polymer Research Dresden and Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg

Published: July 17, Polymers

DOI: 10.3390/polym16142032

Abstract: Thermoresponsive hydrogels were 3D-printed with embedded gold nanorods (GNRs), which enable shape change through photothermal heating. GNRs were functionalized with bovine serum albumin and mixed with a photosensitizer and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm) macromer, forming an ink for 3D printing by direct ink writing. A macromer-based approach was chosen to provide good microstructural homogeneity and optical transparency of the unloaded hydrogel in its swollen state. The ink was printed into an acetylated gelatin hydrogel support matrix to prevent the spreading of the low-viscosity ink and provide mechanical stability during printing and concurrent photocrosslinking. Acetylated gelatin hydrogel was introduced because it allows for melting and removal of the support structure below the transition temperature of the crosslinked PNIPAAm structure. Convective and photothermal heating were compared, which both triggered the phase transition of PNIPAAm and induced reversible shrinkage of the hydrogel–GNR composite for a range of GNR loadings. During reswelling after photothermal heating, some structures formed an internally buckled state, where minor mechanical agitation recovered the unbuckled structure. The BSA-GNRs did not leach out of the structure during multiple cycles of shrinkage and reswelling. This work demonstrates the promise of 3D-printed, photoresponsive structures as hydrogel actuators.

This post was originally published in NC State News.