In Search of New and Better Cancer Treatments

Can researching cancer treatment in dogs and cats have long-term impact on human cancer treatment?

The answer is yes, and the proof is in the work done by Dr. Michael Nolan, associate professor, radiation oncology and biology, and others at NC State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

Nolan is leading research in two separate areas. The first involves clinical trials – testing new cancer treatments in companion animals that have naturally occurring cancer. The second, and where Nolan’s passion lies, is in lab research – studying the complications of cancer treatment to improve quality of life in patients.

“Cancer can cause a great deal of discomfort, and side effects of cancer treatment can also be quite painful. Our goal really is to find ways to prevent, or at least better manage, discomfort that’s experienced by cancer patients,” Nolan said.

For example, the work might help a patient experiencing pain following surgery for cancer treatment, or a patient who develops sores from radiation treatment, he said.

Pain management in cancer patients is challenging because research shows the molecular signaling that’s causing pain is different for cancer, Nolan said. This means the Advil or Tylenol that might work on a headache or muscle strain may not work on pain associated with cancer. Research also shows that when pain is better managed in a cancer patient, his or her long-term prognosis improves, he said.

“Our research is about understanding what those signaling pathways are. By identifying molecular targets, we’ll be able to develop drugs that interrupt the signals, and more effectively treat cancer pain,” Nolan said.

He acknowledges that cancer patients are sometimes asked to endure discomfort because the ultimate outcome of the treatment makes it worthwhile, but he and his team continue to look for ways to improve quality of life for patients as they go through treatment.

Clearly, when Nolan refers to his patients, he’s often talking about dogs, sometimes cats and other animals. However, the research his team is doing could translate to humans.

One current clinical trial, in partnership with Duke University, is taking place on cats with an aggressive form of oral cancer. Duke researchers have developed a new technology for head and neck cancer in people. They began testing in rodents, and the current research with cats is seen as a step on the way to treating humans, Nolan said.

Oftentimes, going from a small animal like a rodent to testing in a human is seen as too big a leap.

“Things are more simple in a rodent, but when you try to scale up to a human, the tolerability, dosing and overall approach changes, so we’ve helped them transition more effectively into a trial for humans,” Nolan said.

“Feline oral cancer is a good model for aggressive forms of human head and neck cancer,” he continued. “By the end, we hope to know how to make this more comfortable and manageable in both species.”

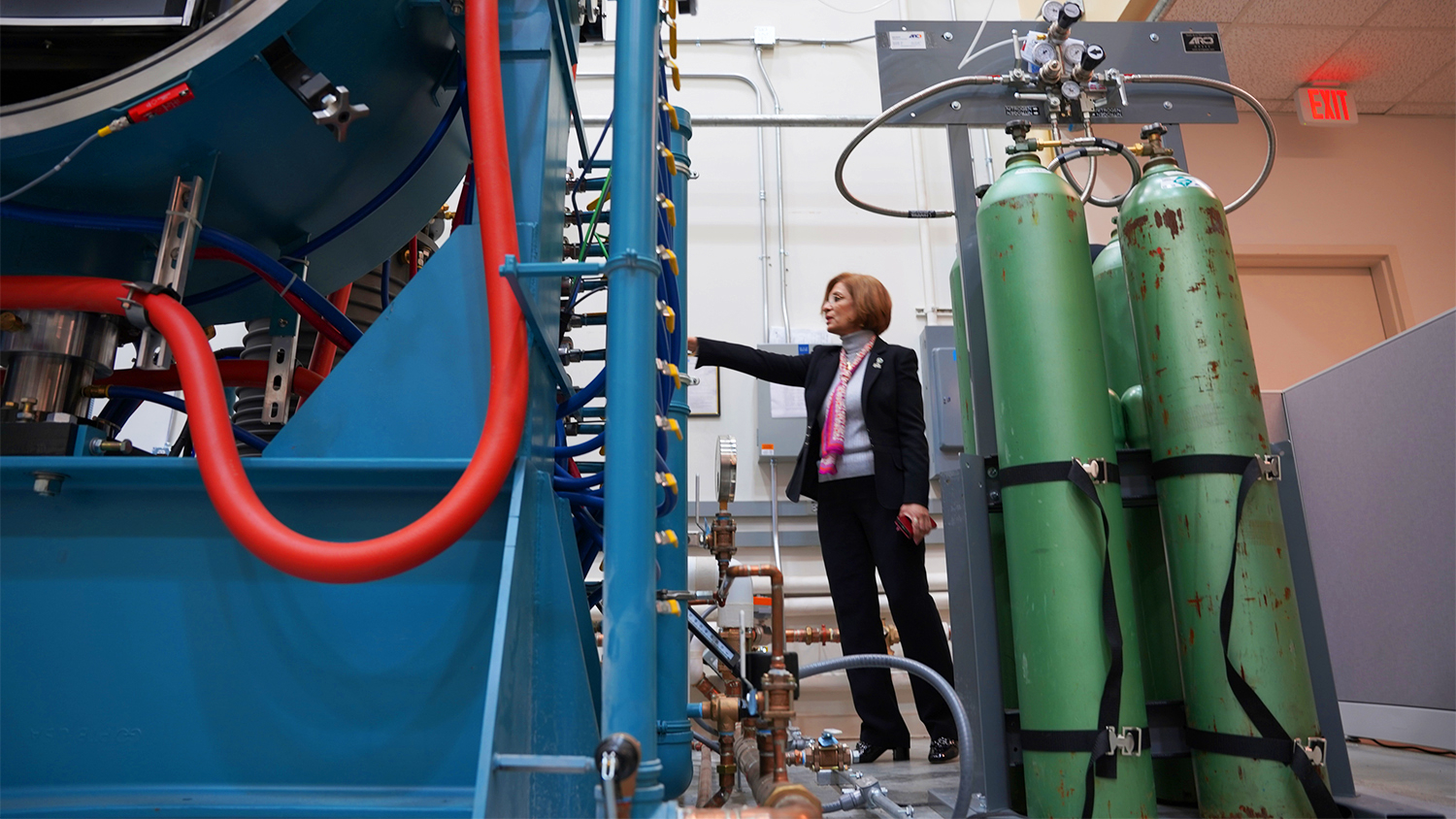

In another case, Nolan is performing research with an industry partner, Immunolight, which had done some research in rodents and came to the College of Veterinary Medicine asking for a canine trial in 2014. To date, the college has used the company’s experimental treatment platform in about 50 dogs, advancing it to a point where a doctor at Duke has, with approval from the federal Food and Drug Administration, now tested the treatment on three human patients.

Nolan’s research is part of a larger comparative oncology program within the College of Veterinary Medicine. Research within the program doesn’t always have a lot of overlap, but Nolan said there’s benefit to multiple comparative oncology projects under one program, providing opportunities for both internal and external collaboration.

He is currently funded through a combination of resources from animal health foundations, internal grants within the college and private donors.

Nolan notes the huge impact private donations have on research.

“They give us a lot of flexibility to investigate new problems, and think outside of the box,” he said. “It could be a new idea and a high-risk project that a granting agency, such as the National Institutes of Health, wouldn’t be excited about until there was a little bit of data behind it. Private funds allow us to accumulate that essential data.

“Private donations are what propel that forward, and give people the flexibility to start acting on the cool ideas that they come up with.”

In a recent interview, Dr. Paul Lunn, dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine, noted just how important translational research like Nolan’s is to the future of medicine in both animals and humans.

“We want to do research that then can be applied in a clinical setting, create cures for animals and cures for people,” Lunn said. “A great deal of basic research is fundamental to any progress we make. But the rubber really meets the road when you see some of these new ideas, new innovations, changing the way that we treat.”

CVM, Nolan believes, can emerge as a world leader in strategies for easing cancer complications and improving treatments. More private and governmental funding can allow researchers to continue to think outside the box, leading to more exciting developments.

“Ideas that can grow into something big have to start somewhere,” he said.

This post was originally published in Giving News.