NC State Alumnus Leads Development of the First Rapid At-Home Test-Kit for COVID-19

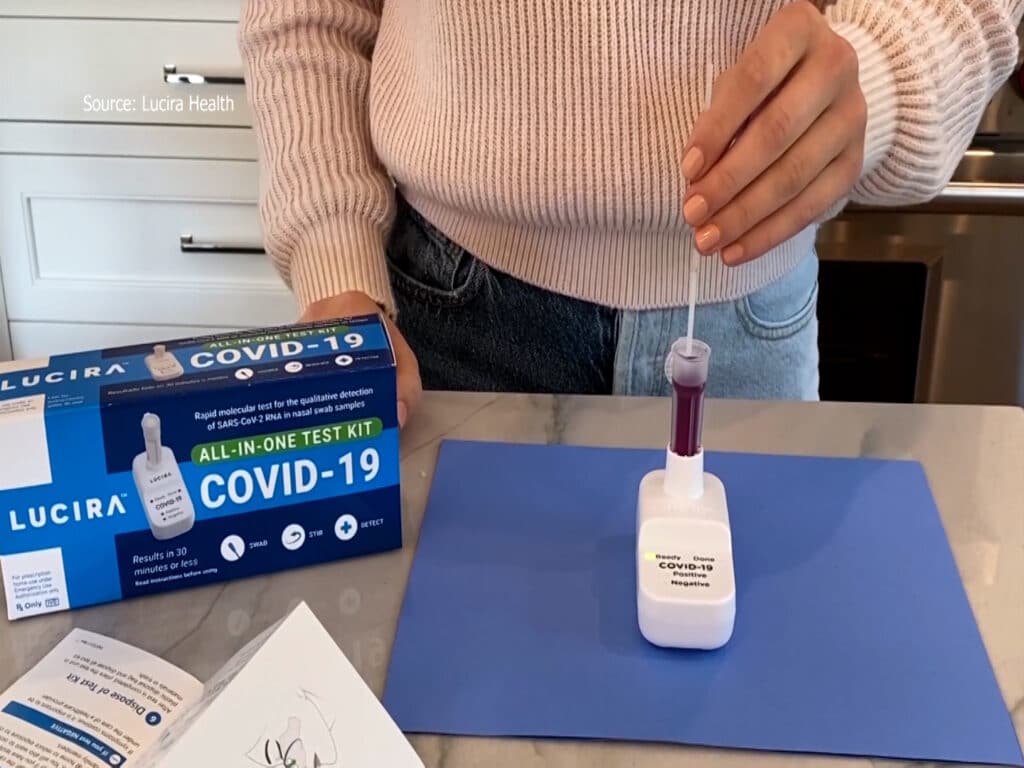

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently authorized the first at-home rapid COVID-19 test-kit by Lucira Health. This could mean shorter lines and waiting periods, which are two major pain points as Coronavirus cases surge across our nation and strain COVID-19 testing capacity.

Frankie Myers, director of engineering at Lucira Health and NC State alumnus led the design and development of the company’s diagnostic platform and shares insights into the innovative process the company took to bring the Lucira COVID-19 All-In-One Test Kit to market.

Recognizing Opportunities

Although the company started working on the COVID-19 at-home test-kit in mid-March, Lucira’s technology had been in development for over 5 years. Lucira Health is a healthcare company headquartered in Emeryville, CA, known for producing disposable test kits to detect DNA and RNA of infectious diseases. In fact, Myers and his team had been working on an at-home flu test prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. “Much of the initial device development and manufacturing process development work was already behind us,” Myers tells us. However, once the severity of the testing challenges brought by the pandemic was evident, Lucira Health quickly pivoted to developing the first at-home test for the dreaded Coronavirus.

The test works by swirling a self-collected nasal sample swab in a vial that is then placed in the test unit. As the director of engineering, Myers led his team through the mechanical, electrical and firmware engineering of the product, working very closely with their assay development* counterparts as well as regulatory, manufacturing, and quality control counterparts. “In the early days of Lucira, I often felt like we were building the plane while flying it – developing our design process while also designing within that process,” Myers admitted. Months of hard work and an unprecedented speed in response from the FDA led to the successful issue of an emergency use authorization for the first Lurica COVID-19 diagnostic test for self-testing at home.

Tackling Big Problems

“With COVID, we’ve seen traditional testing paradigms completely break down,” Myers explained. “During a surge, it’s not uncommon for people to wait over a week to finally get test results back, and that’s after dealing with long lines or limited appointment slots to get tested in the first place.”

As we have painfully witnessed, test results that take that long aren’t very helpful in guiding behavior as individuals can unknowingly continue infecting others as they wait for their test results to come back. “With at-home testing, we give people the power to test themselves and get a result within 30 minutes –– no waiting in line alongside potentially sick people.” This allows test-takers to immediately quarantine if they test positive reducing the public burden of disease transmission.

Lucira’s COVID-19 All-In-One Test Kit is a molecular in vitro diagnostic test that has an analytical sensitivity, or ability to detect the SARS-CoV-2 virus, that is comparable to PCR tests performed in clinical settings and high complexity labs.

But unlike every other molecular diagnostic system out there, the at-home test-kit does not require an instrument to run – eliminating a major bottleneck faced by testing facilities and becoming the first that can be fully self-administered and provide results almost immediately. “Test one person or test a hundred people—all in 30 minutes,” Myers shared.

“Test one person or test a hundred people—all in 30 minutes.”

“I thoroughly enjoyed working with Frankie during his student years at NC State. It was very clear from my first conversation with him that his entrepreneurial mindset would take him places. I’m so thankful that we’ve built programs at NC State that help prepare students like Frankie to achieve their entrepreneurial dreams,” said Tom Miller, Senior Vice Provost for Academic Outreach and Entrepreneurship at NC State.

Below is a Q&A with Frankie Myers, B.S. in Electrical and Computer Engineering, ‘06.

What is your biggest motivator?

For me, challenging the status quo in medical diagnostics has always been the biggest motivation. Why should molecular diagnostics require expensive equipment and trained operators? Why can’t it be inexpensive and simple enough for anyone to use? Of course, it can. Technology has a long history of empowering non-specialists to do things that used to require special training – when’s the last time you needed a travel agent, for example? The pandemic has underscored the need to make diagnostics more accessible.

So we looked at what it really took to run these kinds of diagnostic assays, and we asked “how can we simplify this, both in terms of the technology required and the overall user experience?” This has led us to think critically about engineering tradeoffs across different domains: mechanical, thermal, optical, electrical, software, manufacturing, human factors – in addition to the performance of the COVID assay itself. I really enjoy working through those cross-disciplinary design challenges.

What’s the most daunting aspect of bringing this product to market?

We are moving very quickly to scale manufacturing. That’s challenging with any new product, but it’s particularly challenging when you consider the overwhelming need right now.

I’ll never forget seeing those first shipments go out. This past year has been an enormous effort on the part of so many people—not just within Lucira but for our manufacturing partners as well. It’s humbling and inspiring.

What advice do you have for aspiring entrepreneurs?

Take an honest assessment of what you’re good at and where you will need help. Teams of one rarely do great things. As a founder or an early employee, it’s important to build a team around you that complements you and then empower them to take ownership and contribute to their full potential. Don’t be afraid of change. As the company grows, you’ll need to periodically revisit roles and challenge old assumptions about how you operate.

Often when engineers start companies, they have a technology they are really excited about and they try to fit the product around it. This can lead to a lot of churn. It’s best to really nail down the problem you’re trying to solve while you’re still small and talk to customers to understand their unmet needs.

Then grow the company and focus technical development around those needs. As soon as you can, get a prototype in customers’ hands—even if it’s non-functional—and start collecting feedback. Close that loop, then iterate, iterate, iterate.

What advice do you have for NC State students who want to work in this space?

The regulatory landscape of medical devices can be daunting. Don’t ignore this stuff. There are some great resources out there to help you navigate FDA quality system regulations, for example. It will make you a better engineer. Spend some time at an established company learning how they do things before trying to embark on your own. In the early days of Lucira, I often felt like we were building the plane while flying it (developing our design process while also designing within that process). If you’re going to do this, it helps to have at least been on a plane before.

How did your experiences at NC State prepare you for this role?

I owe a lot to my time at NC State. First, I got a solid electrical engineering education, and I use this stuff every day in the electronic and firmware development of the product.

But more importantly, NC State was where I first learned to work with a team to solve complex engineering challenges. I spent my summers by the pool in Carmichael with the Underwater Robotics Club, designing PCBs, hacking at code, and trying to get this submarine to do barrel rolls. It was rad. We started the club because we were jealous that Duke was doing this and we weren’t. It’s still around!

The Engineering Entrepreneurs Program was also a big influence. It made the idea of building a company seem achievable. As an engineer, the EEP pushes you outside of your comfort zone and gets you thinking about product/market fit, competitive landscape, and fundraising. I’ll never forget our trip visiting NC State founded startups in Silicon Valley. That’s what made me want to come here.

*assay development is a procedure in molecular biology for testing or measuring the activity of a drug or biochemical in an organism or organic samples.

This post was originally published in Entrepreneurship News.