NC State Veterinary Medicine Experts Work to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance

Whether prescribed by a veterinarian or a physician, antibiotics can be a powerful tool in helping patients feel better. Unfortunately, as always, there can be too much of a good thing.

Over-prescribing or misusing antibiotics can lead to antimicrobial resistance that causes therapies to be less effective because the bacteria have developed the ability to defeat the drugs designed to eliminate them. In short, you suddenly have even bigger problems than the reason you sought medical care in the first place.

Preventing the issues caused by antimicrobial resistance starts with good stewardship that emphasizes using antibiotics properly and only when it’s absolutely necessary.

“Antibiotics are the fire extinguisher,” said Dr. Lisa Gamsjäger, assistant professor at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine. “It’s great that we have it, but we need to make sure it’s always functional, and we reserve it for those situations.”

An estimated 1.27 million deaths around the world each year are caused by antimicrobial resistance, and addressing its challenges requires a One Health approach. The NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, through its research and clinical care, is at the heart of the effort.

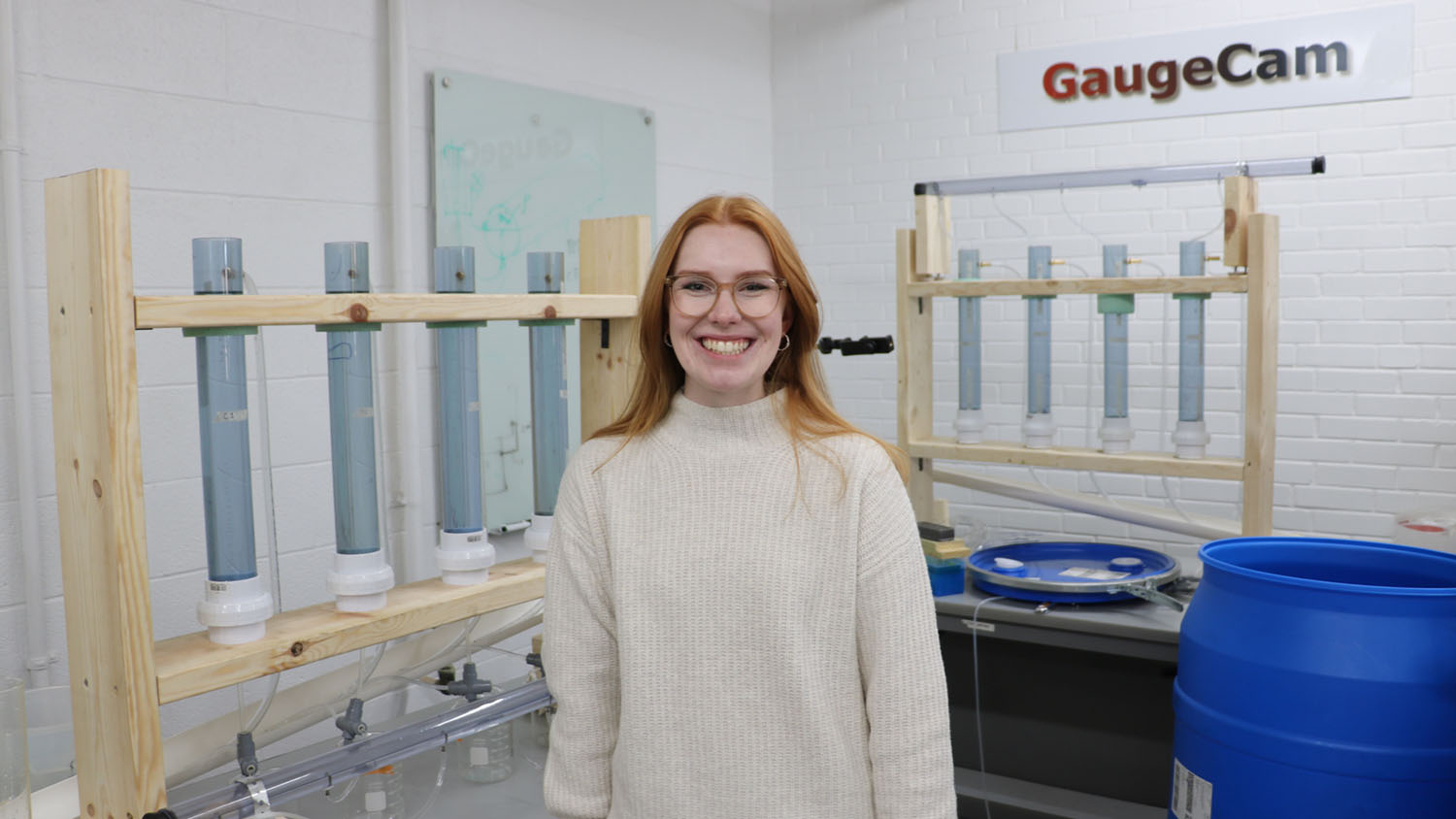

At our veterinary hospital, more than a dozen veterinary medicine researchers and veterinarians are using their expertise to keep our patients and their owners as healthy as possible. In recognition of CDC Antibiotic Awareness Week, Gamsjäger and assistant teaching professor Dr. Erin Frey from the college’s Antimicrobial Stewardship Committee discussed what antimicrobial resistance is, how it occurs, how best to prevent it and how we’re addressing it at our veterinary hospital.

What is antimicrobial resistance, and how does it happen?

Frey: Antimicrobial resistance is when the drugs that are used to treat bacterial infections are no longer effective. This means that we lose our ability to treat animals that are sick, and they develop longer or worse diseases. We have to sometimes then rely on drugs that have more side effects or more costs. And in some cases, there are no other drugs left to try, and we have nothing left to use.

Anytime we use antibiotics — and that is people or pets or farm animals — there’s a chance that the bacteria will then become resistant to that drug, and it won’t work anymore. Even when they’re needed, they can create resistance. So we need to reserve their use for when we need them. People get colds, and antibiotics are not going to help because many colds are caused by viruses. Same thing with animals. A lot of respiratory diseases in animals are also caused by viruses so just because they are sneezing or coughing, you cannot use an antibiotic. They just are never going to work.

Everything that happens in animals also happens in people. Resistant infections can spread between people, but it also can spread between people and their animals or their animals and them. There are more opportunities for infections to spread between animals and people when they live in close contact, for example, when animals live in people’s houses or share their bed, and people who are very young, very old, or immunocompromised are even more at risk. .

Gamsjäger: Antimicrobials have been maybe inappropriately used because, for a long time, they could just be purchased over the counter in a feed store. There wasn’t that much regulation, so now we do have a lot of resistance, especially against those drugs that were available in the feed stores. And as Erin said, a lot of people were using them for viral infections or for things that antimicrobials are not necessarily going to work against.

What’s the best way to combat antimicrobial resistance when, eventually, we all will need an antibiotic for something?

Frey: The first step is to decrease antimicrobial use to only when necessary. That’s the first one. Then, choose the correct antimicrobials and the correct dosage. Underdosing or using a very short or very long timeframe can also impact microbial resistance. So it’s about making educated decisions on how to use those antimicrobials and choosing the right ones.

There’s also reducing the chance that there’s going to be disease. That’s preventive health, which is a core part of veterinary medicine. That is nutrition, good hygiene, vaccinations, how you are going to house the animals and all the things that we do on a daily basis to promote health. We don’t want to be using antibiotics as a Band-Aid.

Gamsjäger: Prevention is really the first step to good antimicrobial stewardship because, if we have healthy animals, we don’t even have to get to that point. Preventative measures are important for all animals, but even more so for farm animals, where we often have a lot of animals housed together in large herds. For farm animals, that’s mostly providing a clean and dry environment, high quality colostrum to newborn animals and a good vaccination program. Establishing a relationship with a veterinarian is a big step. Have your animal or your herd evaluated. Have routine checkups with vaccinations and invest in good nutrition for your animals.

A key way that the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine addresses antimicrobial stewardship at our hospital is through the Antimicrobial Stewardship Committee.

How does this group help keep our patients healthy while addressing these challenges?

Frey: The committee is made up of experts in large and small animals. We have people in different areas — pharmacy, pharmacology, microbiology,, emergency and critical care, primary care, public health, ruminant medicine, surgery, and dermatology, for example. We’re bringing a lot of different people together. Things that we’re doing around the hospital include updating our infectious disease protocols. That includes things such as detection, prevention, treatment and protocols for isolation to keep the animal that’s coming safe and also prevent it from then spreading to other animals. We’re thinking about the health of our patients and also our staff and students handling those patients.

We’ve also been doing these antimicrobial stewardship consults. Anyone in our hospital can send a request to the whole team. And they say, “I have this situation. I have this infection. What drug do I choose? What treatment do I do? Do I need to do surgery here?” That consult request brings the group together and gives individuals access to all of this expertise. Then, we internally have discussions and reach back out.

I think it is important for clients, referring veterinarians and the public to know that we take antimicrobial stewardship very seriously and that our veterinary hospital team is trying every day to make the best decisions that we can for our patients and owners.

When the challenge of combating antimicrobial resistance is so large, what does success look like for the committee?

Gamsjäger: It’s great when I hear students or junior clinicians think about why they’re using an antibiotic, making sure they’re using the right antibiotic, and also thinking about, “Is it going to get where I need it to go? Is it going to go to the organs that are affected? Is it going to be excreted in the way I need it to be excreted?” Just thinking about the antimicrobial choices more and more and more.

But antimicrobial stewardship is way more than just choosing the antibiotic. It’s also thinking about alternative ways to decrease bacterial infection. Oftentimes, we advise flushing and draining the area that’s infected, or surgically removing it or just reminding people that antibiotics are just one pillar of curing the infection. But, for me, people just thinking about antimicrobial stewardship is already amazing.

Frey: Another focus we can have here in the hospital is the training we provide our students and our house officers. They’re going to go out to practice, so my hope is they will carry with them their experience of what they learn here and how they treat cases and then pass that along to their own hospitals or their own teams. If they’re an intern here and they go to be a resident somewhere else, they can share that. They take those resources with them, and then our reach will be well beyond what we have here.

I love hearing students when they come to me in fourth-year in primary care, and they say, “I know I’m not supposed to use an antibiotic for diarrhea.” If someone is taking a moment to stop and think before they’re making a choice, that’s a win.

This post was originally published in Veterinary Medicine News.