The Art of Insect Flight

Adrian Smith spends a lot of time filming and studying insects in motion. He even has a YouTube channel dedicated to the pursuit. And it is fascinating to watch how different insects propel themselves through the air or hop, skip and trundle along the ground.

Recently, Smith worked with photographer and artist Xavi Bou to turn images of insects in motion into photographic works of art. Some of the results are featured in the latest edition of National Geographic Magazine. Smith (who is an assistant research professor of biology at NC State with a joint appointment at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences) and Bou sat down with the Abstract to talk about how the partnership came about, the challenges involved in photographing these subjects, and why they do what they do. You can check out the results of the collaboration below or visit Bou’s website to see more of his work.

The Abstract (TA): How did this partnership come about?

Xavi Bou: I spent the last eight years working on Ornithographies, a project dedicated to revealing the beauty of birds’ flight plans. I decided to expand this visual universe of natural movement to the kingdom of insects. Initially I did some tests in a similar way to what I did with the birds, but it didn’t work.

I realized that I had to change the scale and get much closer to the subjects to appreciate their beauty, but that posed technical problems that I couldn’t solve. Just at that moment one of Adrian’s incredible videos came to me, and I instantly realized that it was exactly what I had been looking for. So after I contacted him about collaborating and he accepted, we worked together to adapt his technique to my needs and thus be able to create the images you are seeing.

Adrian Smith: One benefit I didn’t anticipate from creating and publishing science media online has been collaborations with people outside of my field. When Xavi reached out to me and I saw his stunning work on birds, I knew this would be something worth doing.

Whenever collaborative opportunities like this come up, I’m eager to pursue them. Especially when they are opportunities to bridge my work into different formats and contexts, and to reach audiences I wouldn’t be able to reach on my own.

TA: How long did it take to capture the images – were some insects more “cooperative” than others? How do you stop the subjects from making a break for it?

Smith: I’ve been filming insects in flight to showcase insect biodiversity for the past five years or so. The image sequences captured for this project go back three or four years. I haven’t counted, but I’m sure I’ve captured and published flight sequences of more than 100 different species. Beyond that 100 or so, there have been many that prove to be camera shy or uncooperative in the lab. Even the ones that do fly are not always easy to get images of because a good image sequence is when the insect flies across the frame while staying within a narrow depth of field.

As for preventing escapes, I don’t film in cages or with the insect restrained in any way. I just film everything in a relatively small room with a low ceiling. I have to find and catch the insect in that room after every filming attempt.

TA: Adrian, what is the technology involved in capturing the images? And Xavi, what technique do you use to create the final images?

Smith: On my end of the work, I use high-speed Phantom cameras. For this project most of the sequences were filmed between 1,000 and 6,000 frames per second. The rest of my process is lighting, both to make the image look good and to direct the behavior of the insect. The lowest tech, but sometimes hardest part, is the insect wrangling and handling to both not harm the animal and to get it to behave in the desired way in front of the camera.

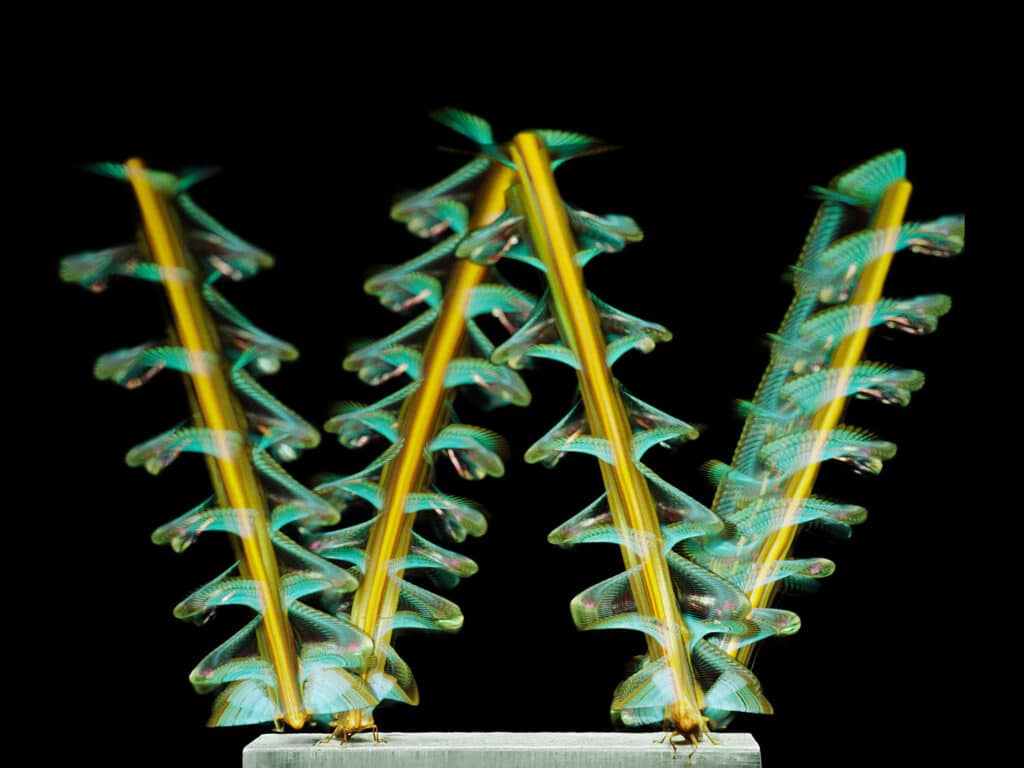

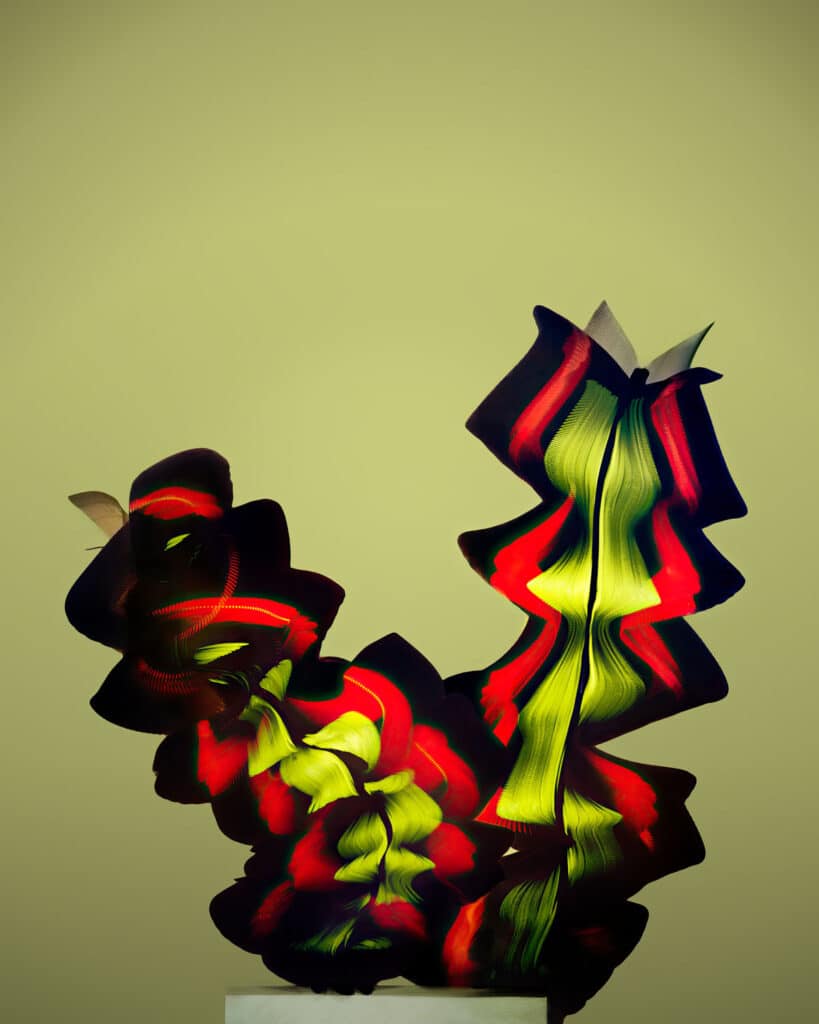

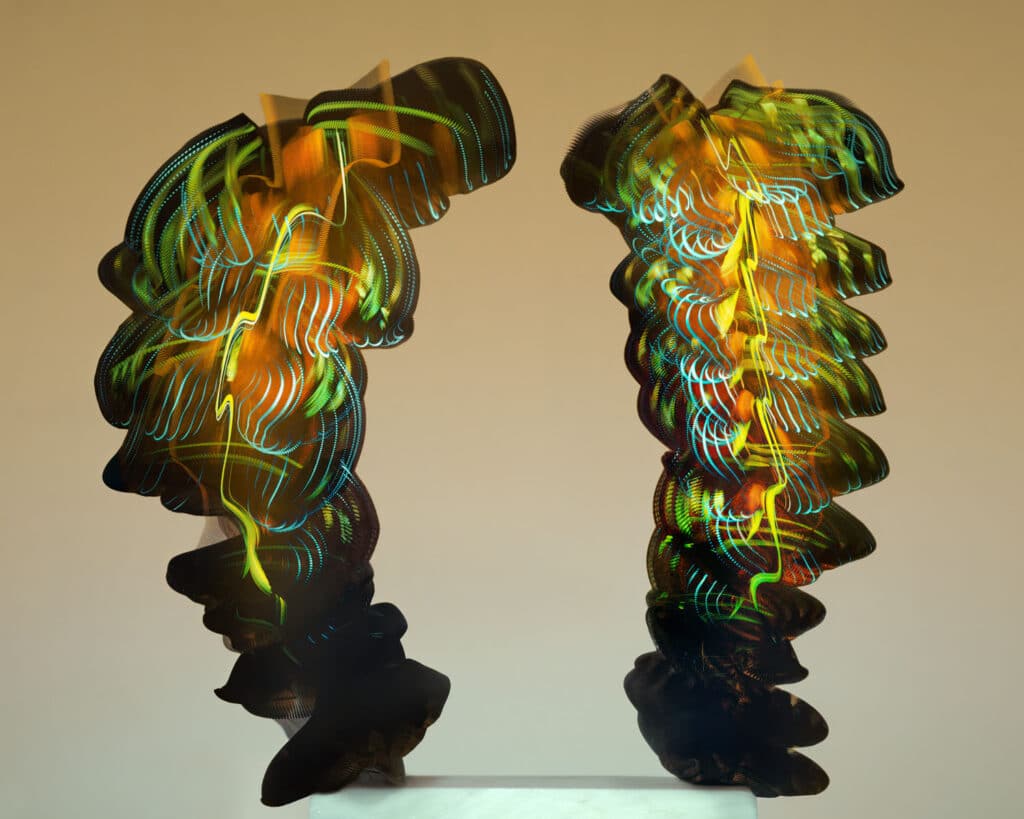

Bou: The process is quite similar to the one I use on birds: by merging frames from Adrian’s video sequences with algorithms we stop seeing an insect in flight. These very organic shapes appear, which are suggestive of sculptures or flowers.

The idea of engraving them on a pedestal comes from wanting to value, as if it were a trophy, this animal kingdom that goes so unnoticed and that is disappearing without many of us realizing it.

TA: How many “takes” did you need on average to get the images?

Smith: A good session where I end up with 3-4 good flight sequences from a single species takes about 2 hours on average. In that time, I’ve probably recorded and scrapped two or three times as many sequences as the ones I’ve saved.

TA: Do you have any plans for future projects?

Smith: Yes, I hope to continue collaborating with Xavi on this and similar projects. My work filming and producing public media about insects and science is always ongoing through the Ant Lab YouTube channel, across other social media platforms, and through a long-time collaboration with the SciNC show on PBS-NC. I also have a few additional art/science projects that are in the works (including a series of physical flip books that I am very excited about), but those are not yet ready for show quite yet.

This post was originally published in NC State News.